Print Matters

This research was conducted by Farshore Insight (formerly Egmont Insight).

One year on from HarperCollins UK’s acquisition of Egmont Books (formerly Egmont UK Ltd) from the Danish Media Group, Egmont, we are delighted to announce our new identity: Farshore.

Children’s leisure time is dominated by screens, yet when it comes to children’s eBooks and book apps, sales have not taken off. In fact, they have declined: eBook volume share has decreased to 11.3% in 2015 from 13.2%in 2014. Over 70% of those children’s eBooks are bought for age 17+ (Nielsen 2015). Meanwhile, the children’s print book and magazine markets are in good health up 7% and up 5% in value respectively, year on year (2015 vs 2014).

There is a great deal of evidence illustrating why stories and reading are so very important to children, including impact on educational success, developing empathy, imagination, vocabulary and so on. Clearly stories and reading are not the sole domain of print, yet despite the appeal of the digital world, there seems to be a consistent fondness for print. Various studies (in the UK and around the world) have shown that parents and children, including teenagers, prefer print books to eBooks. In the UK, 73% say so (Nielsen 2015).

Why is print preferred? What does print offer to children and to families? Is it offering something beyond the story itself? Do parents and children respond differently to reading and being read to in print and in digital? If so, how does it feel?

The Research

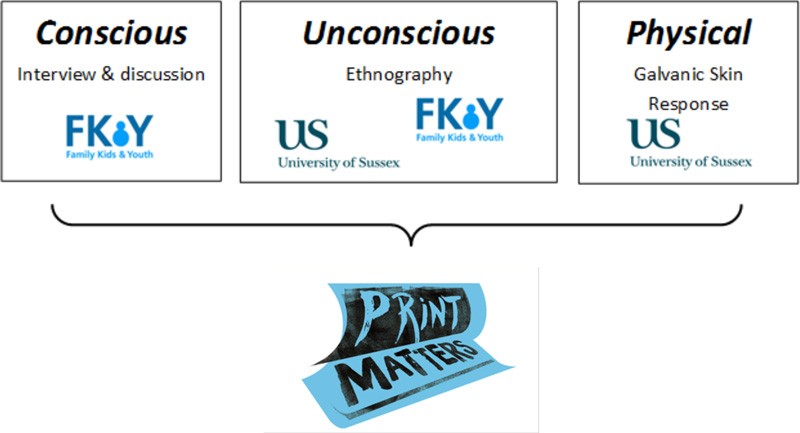

Print Matters explores parents’ and children’s responses to reading children’s books (print books, eBooks and apps) and magazines. We commissioned two studies and worked with Family Kids and Youth and with The University of Sussex’s Children and Technology Lab, part of the School of Psychology. In total, the sample was 43 parents and 43 children ranging from 2-9 years old. Using interviews and discussion, observation and Galvanic Skin Response, the findings of the two investigations are brought together to form a view of the conscious, unconscious and physical responses to reading.

Conscious Response

Emotional response to reading

Many parents are very busy and feel guilty about not spending enough time with their children. Reading, especially at bedtime, provides quality moments when attention is focused on the child. Several parents talked about their children opening up and telling them about their day. Reading therefore becomes an opportunity for closeness. Reading with children feels very nurturing and bonding for parents. It’s cuddly time and contributes to a feeling of a safe and happy home. These warm feelings are echoed by the children themselves. Mums said that reading with their children makes them feel that they are being a good mum, a real mum, a nurturing and caring mum. It was described as positive and affirming, even a validating experience. Parents’ own nostalgia plays a big part in their desire to read to their children. They talked about memories of being read to, remembered feelings of enjoyment, being held and the fun of talking about the story. They recalled feelings of being ‘loved’, ‘safe’, ‘secure’, ‘happy’ and ‘close’ to their own parents when they were read to.

‘I feel like I am soothing and making him feel relaxed, safe and secure with my voice . . . I remember my dad’s voices’

Mum of 4-year-old boy

Why do printed books and magazines appeal?

We found that parents value print books and magazines for providing quality time with their children and welcome time away from screens. While parents embrace quality digital entertainment for their children, they are keen for them to have some time off screen too.

Print books are appreciated for their physicality: parents like the feel of print, even the smell of it. And they like the look of books – aesthetically pleasing, books bring a homely feel and the impression of an intellectual household. Print is part of the bedtime routine and the physical book prompts bonding and cuddling. Touching and turning the pages together is enjoyed by both parents and children. Parents find passing the book around is good when reading to more than one child. Larger formats and plenty of illustrations allow for better sharing, and this is especially true for younger children. With print parents feel relaxed, involved and necessary to the reading experience.

Print books are appreciated for their physicality: parents like the feel of print, even the smell of it. And they like the look of books – aesthetically pleasing, books bring a homely feel and the impression of an intellectual household. Print is part of the bedtime routine and the physical book prompts bonding and cuddling. Touching and turning the pages together is enjoyed by both parents and children. Parents find passing the book around is good when reading to more than one child. Larger formats and plenty of illustrations allow for better sharing, and this is especially true for younger children. With print parents feel relaxed, involved and necessary to the reading experience.

Because printed books are familiar and visible, children can look, choose, touch, and initiate reading by taking one to Mum or Dad to read. Children enjoy organising, sorting, repeat reading, collecting (part of child development) and print books enable this.

Print books can become very significant in themselves – precious objects that represent powerful emotions. They trigger feelings of being cherished and cared for. Parents love the idea of passing books down, much as a family heirloom. It seems the physicality of the object jogs memories of their own childhood experience.

‘I want to keep the books forever, until they have their children. They have a past and a life which is very different to a tablet,’

Mum of 3-year-old boy

Parents also value the physicality of magazines, appreciating that they offer time away from screens and that they enable them to spend time doing activities and reading with their children. They value the package a printed magazine offers: activities and creativity, stories, a free gift and entertainment rolled into one – ‘a treat with benefits’ – offering reading practice ‘by stealth’. One mum said of her 6-year-old son, ‘He doesn’t even realise he is reading when he has his magazine.’

What are the benefits of digital reading?

Children enjoy screen time and parents have mixed feelings; they appreciate book apps for entertainment, education/soft learning and they want their children to be digitally literate. However, they are also anxious about their children having too much screen time. eBooks and book apps are extremely useful as a babysitter and the study found that digital reading is most often a solo experience for children – a substitute for parents, used when they don’t have time to read to their child.

As part of the study, parents were asked to use eBooks and book apps to read to their child. Parents found that the interactive elements can interrupt the story. This was especially true with younger children, who wanted to follow the text with a finger (as did the parents), which caused pages to turn when they didn’t want them to. Parents were heard saying ‘don’t touch’/‘leave it alone’ and the device became a distractor that was very much ‘present’ in the reading experience: parent, child, device and story. When reading print, this was simply parent, child and story.

Some children in the study didn’t want to be read to from a device. As many are used to using digital entertainment on their own and having control of it, they have a proprietary feeling about devices and want them for themselves. One mum commented, ‘I feel redundant!’

Unconscious Response

Ethnographers’ observations

As well as speaking to parents and children about their experiences of reading, ethnographers observed them reading together in order to analyse the unconscious signals given off through body language. Ethnographers observed that print books enable better eye contact. A device is, fundamentally, a ‘head down’ experience: both parent and child tend to be focused on the screen. This is reinforced if it’s a book app with audio, where the sound comes from the device. By contrast, when a parent is reading a print book the sound comes from the parent, so the child tends to turn their head to look where the sound is coming from. When reading to multiple children parents turn a print book around and show the pages. In so doing, they all look at each other. This was not observed when reading from a device.

Ethnographers noted that print books enable closer physical contact between parent and child – simply sitting with an arm around a child is easier than when using a reading device. Closeness is a significant part of the appeal of print. When we are touched and embraced we release oxytocin (the ‘cuddle hormone’), which makes us feel safe and attached, reinforcing emotional bonds. Oxytocin is also released when we touch ourselves – it’s a subconscious reassuring and calming mechanism. So it was interesting to observe that a child’s physical movement is a striking feature of being read to. This, coupled with being cuddled by a parent, seems to tap deep into the unconscious, evoking feelings of security, being looked after and cherished.

A direct comparison between print and digital

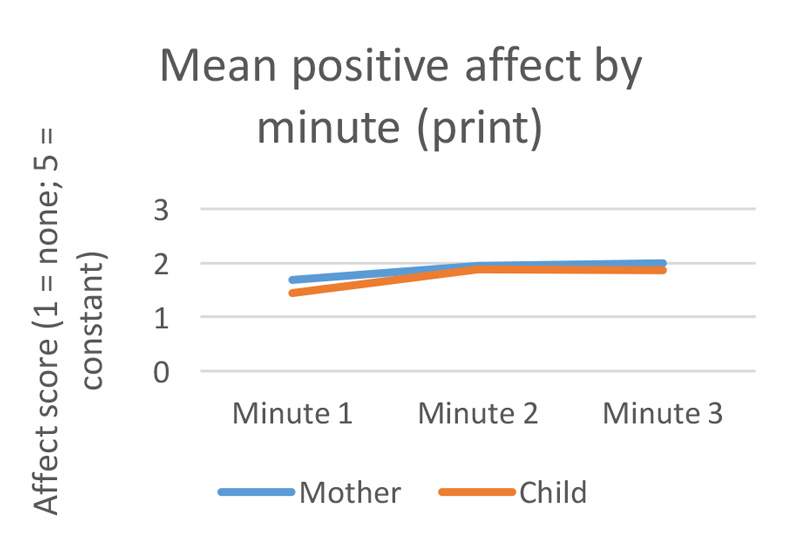

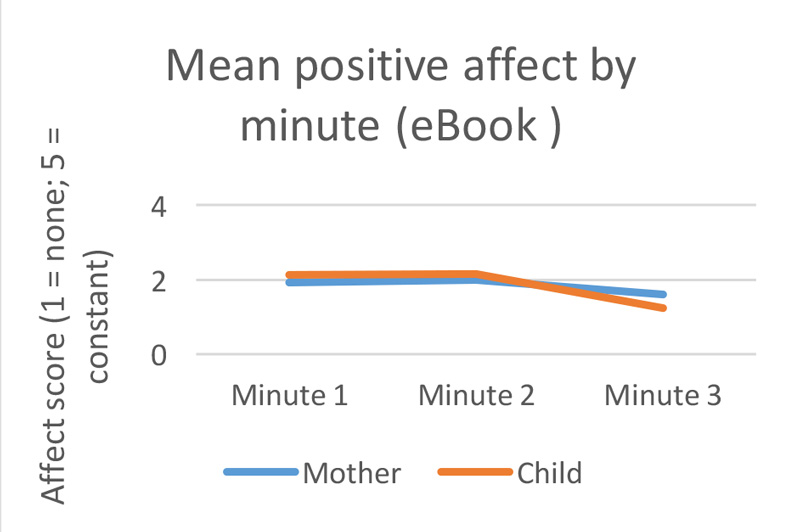

The University of Sussex’s Children and Technology Lab measured differences in emotional response to print and to digital by observing 19 mother-child pairs reading the same text together at home. The children were aged between 7 and 9 years old and had free choice of reading Barry Loser or Mr Gum. They read one chapter on screen and one from the print book, in randomised order. They were filmed and ethnographers reviewed the first 3 minutes of the print and of the screen experience, looking for signs of positive emotion and interaction.

The findings suggest that most parents and children prefer reading print books, rather than stories on a screen. Video analysis showed that the physical closeness that print books enable was accompanied by increasing emotional warmth as reading continued (Graph 1). Children displayed squirming movements such as gripping and squeezing toes and rubbing their arms, which supports the idea that reading books is physically calming as well as imaginatively engaging. As both parent and child got into the story, warmth and positivity increased. The eBook interaction showed that emotional warmth dropped over time (Graph 2). It was interesting to see that the level of emotional warmth was a little higher for the eBook at the start. Perhaps this was the anticipation of reading digitally or because children associate screens with a lot of fun, heightening expectations. Despite this, warmth drops. This could be to do with frustrations with the device (parents saying, ‘don’t touch that,’ children not able to follow the text or point to pictures without the pages turning etc.) or perhaps it’s an indication of slightly less cuddling and so less feel-good oxytocin being produced.

Physical Response

Galvanic Skin Response

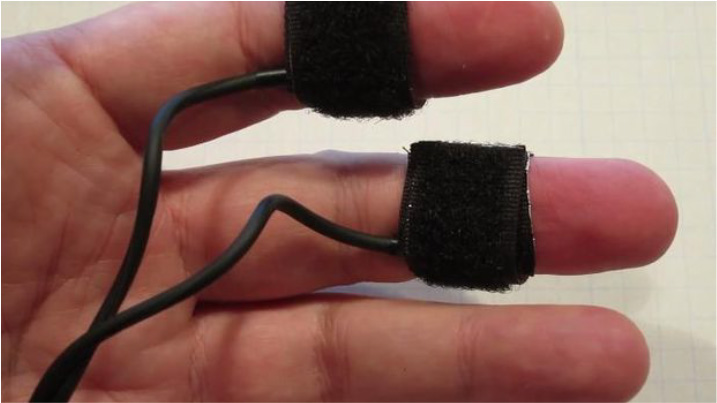

The emotional response to books and reading is clear from parents talking about how they feel and through ethnographers’ observations. We wanted to understand if there was also a physical reaction to reading. Working with the University of Sussex’s Children and Technology Lab, using Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), which measures skin conductance (sweating) through sensors attached to the hand, emotional arousal was measured.

The emotional response to books and reading is clear from parents talking about how they feel and through ethnographers’ observations. We wanted to understand if there was also a physical reaction to reading. Working with the University of Sussex’s Children and Technology Lab, using Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), which measures skin conductance (sweating) through sensors attached to the hand, emotional arousal was measured.

GSR was originally used by Jung. He conducted a study where a list of words was read to the participants. He noted that if a word was emotionally important, the skin responded. Simply put, increases in skin conductance indicate higher emotional arousal. Arousal can be positive or negative.

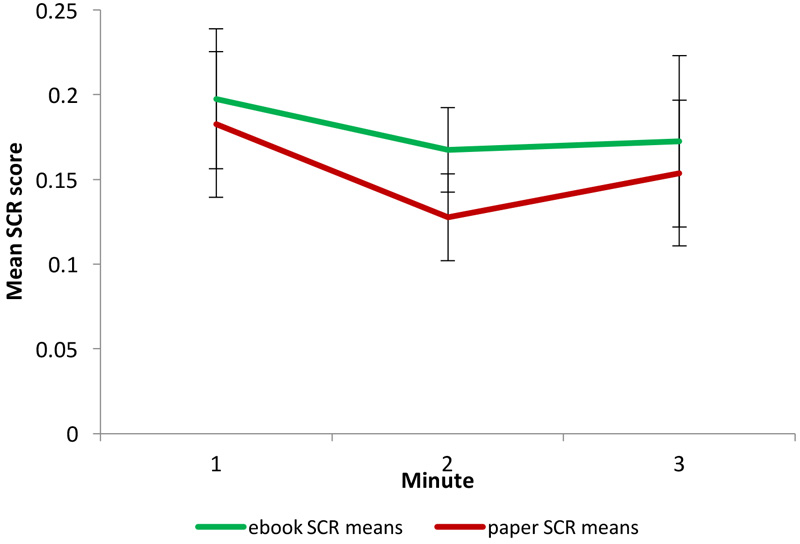

The green line shows the response to digital: there was a slightly higher arousal than with print. It reduces slightly over time, but not a lot. Perhaps, as with the ethnographers’ observations, this is indicating excitement, more anticipation, more ’buzz’. But arousal can be negative too, so it may indicate more frustration and adrenaline. The skin response to print (the red line) reduces more over time– dipping at two minutes. The really interesting comparison is that when this is viewed alongside the Graph 1 findings for reading in print, arousal drops just as observed signs of positive engagement go up. Going back to touch and to the release of oxytocin, when oxytocin levels go up, heart rates go down. These findings suggest something about the calming nature of being read to in print.

Conclusion

Reading is an emotional experience. For parents, reading to their children is nothing less than an expression of love. eBooks and book apps work well for the child’s solo use and print is preferred for reading together. Print helps parent and child to be physically close; it encourages cuddles, works well for sharing and for bedtime, encourages eye contact and facilitates quality time together. For children, being read to is so much more than the story. It’s fun, deeply reassuring, calming and bonding. Observed emotions and attachment are stronger than with digital. Unconsciously, both parents and children respond at a visceral level to print. The power of print is, in part, about the power of touch, which comforts children and makes them feel secure. Cuddles and oxytocin reinforce the positive emotional experience of being read to.

The very fact that digital entertainment is so prevalent is another reason why printed books and magazines are valued by parents: they provide time off screen and quality time together. Why are they loved by children? Apart from enjoying basking in parents’ attention, the hugs and reassurance, there is an important point about the physicality of books and magazines. Collecting, owning and sorting is a key part of child development. In a world dominated by digital leisure time, children may feel even more need to have physical things. This is perhaps one reason why TV characters and digital brands licensed into print work so well. The digital world may be much more ‘current’, but it’s not all about that. Children want both immediate (online) access to the authors, illustrators, brands and characters they love and physical representations they can hold on to.

It is clear that print books and magazines remain as relevant to parents and children as ever, and that they offer something more than the stories and content found within. They enable parents and children to spend precious time together, and they bring about a deeply emotional response. Reading with children is an expression of love. Considering this, it is perhaps no surprise that print continues to outsell digital in the children’s market. Print matters.